SNAP and Obesity: The Facts and Fictions of SNAP Nutrition

As the emphasis of the SNAP program has moved towards nutritional support and education, there has been greater interest in assessing the nutritional impact of SNAP. In general, Americans living at or below the poverty level tend to have a less healthy diet, as calculated by the Healthy Eating Index (a USDA metric that measures dietary intake compared to a national nutritional guideline baseline). While the SNAP program has been successful in reducing food insecurity, some wonder whether SNAP is as nutritionally beneficial. Here we have assembled relevant information on the role of SNAP in the nutrition of Americans, and areas where there is room for improvement.

Does SNAP contribute to obesity?

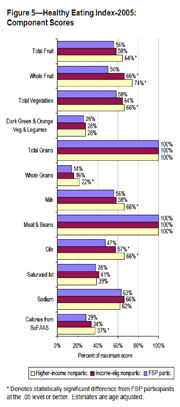

Nutrition intake of SNAP participants and non-participants according to the USDA in 2005.

Many critics of the SNAP program have accused it of encouraging unhealthy eating habits among its participants and contributing to increasing rates of obesity in the United States. Such critics believe that the mere distribution of food assistance leads SNAP recipients to buy more food, which results in higher consumption among the SNAP population. Others think foods high in sugar and fat content that contribute minimal nutritional value are cheaper, and are therefore more likely to be purchased with SNAP benefits. A 2007 study conducted by the Economic Research Service at the USDA found that these claims are, for the most part, false. No trend was seen when rates of obesity and overweight were compared between SNAP participants and non-participants at the same income level for the majority of the SNAP population.

However, the same study found that among the nonelderly female population, participation in the SNAP program did correlate with higher obesity and overweight rates. In fact, for such women, participation in the program for a 1- or 2-year period resulted in an increase in the likelihood of being obese by 2-5%. This is equal to a gain in Body Mass Index (BMI) of 0.5%, about 3 pounds. Long-term participation in SNAP for these women corresponded to a 4.5-10% increase in the probability of being obese. Nonelderly females make up around 28% of SNAP recipients nationwide.

A 2010 study completed by the Harvard School of Public Health using the 2007 Adult California Health Interview Survey (which tracks Body Mass Index and obesity data among Californians) found that obesity rates among SNAP participants were 30% higher than among non-participants, when adjusted for socio-demographic characteristics, food insecurity, and participation in other programs.

SNAP has been associated with higher obesity rates among some subpopulations (particularly adult females), but shows no contribution to obesity among other populations.

At the same time, there are numerous studies that have found a positive contribution of SNAP towards nutrition. Researchers have found that SNAP benefits increase a household’s overall dietary quality, as measured by the USDA Healthy Eating Index. Children who participate in SNAP have been found to have higher levels of essential vitamins and minerals, like iron, zinc, niacin, thiamin, and vitamin A.

The same children also have lower rates of nutritional deficiency than children at comparable economic levels.

Clearly, more data is needed to determine the relationship between SNAP, obesity and nutrition. But whether or not SNAP contributes to obesity, the program still presents an ideal opportunity to improve nutrition in the United States. With more than 45 million people currently enrolled in the program, any changes made to make SNAP more nutritious would have a broad and significant impact.

Improving SNAP Nutrition: Areas of Interest

So we want to improve SNAP nutrition—where can we begin? It isn’t as simple as just focusing on cost and health. Studies show that people will choose foods that contribute minimal nutritional value, even if those foods cost just a little bit more and are worse for your health in the long run. Eating habits are influenced by a wide variety of factors, including socio-economic and demographic characteristics, ethnic or familial traditions, convenience, advertising, and even biological triggers that make us more prone to eating foods high in sugar, salt, and fat. Thus any reforms made to the SNAP program have to take into account human behavior; changes that seem rational may not actually be effective in increasing nutrition of SNAP clients.

First of all, a report commissioned by the USDA found that simply increasing the SNAP benefits of participants—under the assumption that having more money would allow SNAP users to purchase higher cost nutrient-dense foods—did not result in an increase in the consumption of these foods. Other purchases tend to take precedence over healthy eating, unless income increases significantly. Instead, behavioral economics indicates that financial incentives for healthy foods like fruits and vegetables are more effective. Giving SNAP participants coupons or money back when they purchase produce does result in higher consumption of fruits and vegetables; but even then, SNAP participants do not consume as many fruits and vegetables as recommended by federal guidelines.

A more innovative and successful approach to reforming SNAP may involve changing how foods are purchased. SNAP users offered the option of pre-ordering food baskets (instead of taking trips to the grocery store) bought significantly more healthy foods and fewer unhealthy foods. Giving SNAP participants the option of choosing when their SNAP benefits arrive (e.g., monthly, biweekly, or weekly) can also increase the purchase of healthy foods, as perishable items can be purchased more easily. Studies show that providing SNAP clients with a “suggested” budget for their SNAP benefits (e.g., allocate $40 for leafy green vegetables) can help SNAP users spend their money more wisely. And distributing low-cost bowls and dishes with visual graphics that represent recommended portion size may be a more productive use of SNAP-Ed resources.

Sources:

Guthrie, J. F., Lin, B.-H., Ver Ploeg, M., & Frazao, E. (2007). Can Food Stamps Do More to Improve Food Choices? U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Economic Information Bulletin 29-1. (USDA Report)

Ver Ploeg, M., L. & Ralston, K. (2008). Food Stamps and Obesity: What Do We Know? U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Economic Information Bulletin No. 34. (USDA Report)

Leung, C. W., & Villamor, E. (2011).Is Participation in Food and Income Assistance Programmes Associated with Obesity in California Adults? Results from a State-Wide Survey. Public Health Nutrition. 14(4): 645-52.

Food Research and Action Center. (2011) A Review of Strategies to Bolster SNAP’s Role in Improving Nutrition as well as Food Security. (Report)