New Nutrition Standards for School Lunches

February 15, 2012At a visit to Parklawn Elementary School in Virginia on January 25th, 2012, First Lady Michelle Obama announced the new nutrition standards set by the USDA for school meals.

“When we send our kids to school, we have a right to expect that they won’t be eating the kind of fatty, salty, sugary foods that we’re trying to keep from them when they’re at home,” Mrs. Obama said. “We have a right to expect that the food they get at school is the same kind of food that we want to serve at our own kitchen tables.”

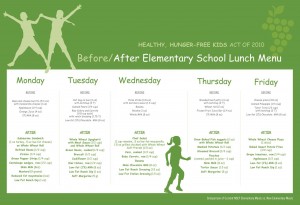

The new USDA nutrition standards will ensure that students are offered both fruits and vegetables every day of the week at school, considerably increase servings of whole grain foods, limit milk to only fat-free or low-fat varieties, determine calories based on the age of children to ensure proper serving size, and reduce the amounts of saturated fat, trans fats and sodium.

The nutrition standards are just one component of the Healthy Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 that aim to reshape meals in American schools. The 2010 legislation has also extended the application of these nutrition standards to other foods sold in schools that aren’t directly subsidized by the federal government, which include “a la carte” food products on the lunch line and snacks in vending machines. To help cover the costs of the changes, schools that fulfill these new standards will receive an extra six cents per meal, which is the first change that has been made to the reimbursement rates for school meals in the last three decades.

While the new guidelines have been highly anticipated, the path to the long-awaited release of the nutrition standards has not been smooth. In 2011, heated debate in Congress arose when it passed a law preventing the limitation of servings of starchy vegetables like potatoes to twice per week, and again when it approved legislation qualifying two tablespoons of tomato paste, the amount typically used on pizza sauce, as a vegetable serving.

However, most public health advocates and Administration officials are enthusiastic for the newly established guidelines, calling the standards an important step forward in improving nutrition in public schools. “We applaud the U.S. Department of Agriculture for issuing final guidance to help schools across the country serve healthier meals to students,” said Jessica D. Black, Project Director for the Kids’ Safe and Healthful Foods Project, a joint initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Kevin Concannon, the USDA’s Undersecretary for Food, Nutrition and Consumer Services, emphasized his hopes for the standards, stating “I am confident we have a core set of healthy diets for children”.

That is not to say there are no dissenting views. The National Potato Council still has some concerns about the standards, stating that “the potato is being downplayed in favor of other vegetables in the new guidelines”. In light of last year’s Congressional activity though, the new standards have generally received support from the food industry. Corey Henry, Vice President for Communications of the American Frozen Food Institute, said that “the new rules improve school nutrition, but at the same time give schools the flexibility to serve a variety of foods to meet the standards,” marking “[a] balanced approach that meets the goals of everyone involved.”

Despite the support that the new nutrition standards have garnered, there has been increasing controversy about whether kids will actually eat the healthier meals prescribed by these recommendations. The Los Angeles Unified School District’s changes to their school lunch menu at the start of the school year were poorly received. Instead of getting students to eat healthier food, participation in the school lunch program dropped sharply, and the LA Times reported that massive waste resulted from untouched foods being thrown away. Furthermore, some students were ditching lunch, while at other campuses, an underground market for chips, candy, and other junk foods emerged.

A similar situation occurred in Chicago, where cafeteria workers held a demonstration, expressing their concerns about the changes made to the city’s school menus. A recent report surveying lunchroom workers titled “Feeding Chicago’s Kids the Food They Deserve” revealed that a significant amount of healthy foods were left uneaten.

However, we should not give up on getting kids to eat healthy food. Rather, the problem here is one of broken communication. For instance, the same report on Chicago schools found that 75% of the cafeteria workers said they were not given a chance to provide any input on the new menu, and that 62% requested nutrition education training so they could better communicate with students. School administrations must foster greater exchange and dialogue with both students and lunchroom staff, asking for feedback and incorporating these recommendations into their menus. Children will be much more likely to eat what they are familiar with, and more knowledge about nutrition definitely wouldn’t hurt!

The quest to improve nutrition in schools is challenging. But it also provides an opportunity for education to ensure that nutritious foods are offered in schools and eaten by kids. Including students in the process of learning about nutrition and designing school meals is an important component of success!

Comments are closed.