U.S. Farm Bill: Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Farm Bill?

The U.S. Farm Bill is a comprehensive piece of legislation that covers most federal government policies related to agriculture in the United States. The Farm Bill is typically renewed every five years.

The provisions of the Farm Bill are divided into what are called “Titles”—overarching categories related to food and farming in the U.S. The 2014 Farm Bill had 12 titles: commodities; conservation; trade; nutrition; credit; United States rural development; research; forestry; energy; horticulture; crop insurance; and miscellaneous. New titles can be added to the Farm Bill during the re-authorization process; the Energy title, for instance, was created in 2002.

What is the history of the Farm Bill?

The Farm Bill was originally created in 1933 as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Agricultural Adjustment Act, which provided subsidies to U.S. farmers in the midst of the Great Depression. The federal government paid farmers to stop the production of seven main crops—known as “commodities”—in the hopes of decreasing the supply and thus increasing the prices of staple crops. The Act also contained several provisions related to conservation, support for farmers suffering from effects of the Dust Bowl, and the storage of surplus harvests.  Although the Act was later declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court (the tax structure used to fund the program was deemed an overreach of the powers of the federal government), its basic premise was included in later Agricultural Adjustment Acts and eventually became the basis for all future U.S. Farm Bills. Since 1965, Farm Bills have been passed with general consistency every five or six years.

Although the Act was later declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court (the tax structure used to fund the program was deemed an overreach of the powers of the federal government), its basic premise was included in later Agricultural Adjustment Acts and eventually became the basis for all future U.S. Farm Bills. Since 1965, Farm Bills have been passed with general consistency every five or six years.

How is the Farm Bill created?

The Farm Bill comes up for renewal every five years or so. Congressional negotiations on what to include in the bill typically take about two to three years, although talks may last longer if parties can’t come to an agreement.

Discussions begin in the House and Senate Agricultural Committees, where hearings are held to review current policies, introduce possible changes to the legislation, and determine funding strategies for any revisions. These discussions generally are held two years before the deadline for re-authorization. At the same time, representatives from Congress hold meetings with trade organizations, farm lobbyists, and civil society organizations who have interests in the contents of the Farm Bill. Lawmakers also conduct regional and local town hall meetings to gather input from their constituents about the Farm Bill.

While Congress prepares, the White House and the U.S. Department of Agriculture set out their own plans for revisions to the Farm Bill. Officials from each agency conduct research, talk to key stakeholders, and generate proposals for legislation or policy briefings to submit to Congress when the bill comes to table. Congress has the final say on the content of the Farm Bill, but these proposals and briefings can play an important role in shaping congressional negotiations.

After the final round of hearings in the Agricultural Committees, drafting of the Farm Bill begins. A finalized version of the bill is produced by both Senate and House Agricultural committees, and is sent to the House and Senate floors for penultimate discussions. A joint version of the Farm Bill is produced, voted on by both congressional bodies, and sent to the president for signature to pass the bill into a law.

However, the current debate surrounding the national deficit has resulted in some changes to this process. In late November of 2011, the Agricultural Committees completed a bipartisan, bicameral proposal for consideration by the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction (more commonly known as the Super Committee). The bill proposed $23 billion in cuts over 10 years, including $4 billion to be trimmed from SNAP by eliminating automatic enrollment for those qualifying for energy benefits. The Super Committee had the authority to fast track the bill’s approval, or to scrap it entirely.

But now that the Super Committee has failed to reach an agreement, the Farm Bill will be subject to a conventional legislative process that may, or may not, use the Agricultural Committees’ proposed bill as an initial draft. The failure of the Super Committee will also trigger automatic cuts beginning in January 2013. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the Farm Bill could bear up to $15.6 billion of these cuts. However, the automatic cuts exempt assistance programs including Medicaid, Social Security and SNAP.

Who are the main players in the Farm Bill?

Many individuals and organizations contribute to the Farm Bill, including members of government and special interest groups, which span a broad range of issues. For instance, key industry groups include the American Farm Bureau Federation, the National Corn Growers Association, and the International Dairy Foods Association. A diverse set of advocacy organizations also play an important role, such as the Center for Rural Affairs, the Environmental Working Group, and the Food Research and Action Center, among others.

Within Congress, several committees play a central role in Farm Bill negotiations, including the chairs of the House and Senate Agricultural Committees; the chair and members of the Senate Sub-committee on Hunger, Nutrition, and Family Farms; the chair of the House Nutrition and Horticulture Sub-committee; the chair and members of the Senate Sub-committee on Production, Income Protection, and Price Support; the chair and members of the House Sub-committee on General Farm Commodities and Risk Management; the head of the House Hunger Caucus; and the chair and members of the House and Senate Appropriations Committees.

How much does the Farm Bill cost?

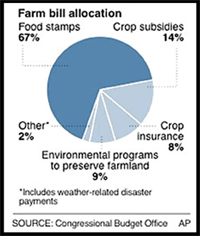

The 2014 Farm Bill provided $489 billion in mandatory spending over the next five years (this figure does not include discretionary spending measures that are approved separately). Nutrition programs account for 80% of spending, followed by crop insurance (8%), conservation (6%), and commodity programs (5%). The remaining one percent included trade subsidies, rural development, research, forestry, energy, livestock, and horticulture/organic agriculture.

According to the Congressional Research Service, the 2014 Farm Bill restructures support for traditional commodity crops—grains, oilseeds, and cotton—by eliminating direct payments. Currently, most support for farmers comes from crop insurance programs in which farmers only receive payments when prices or revenues decrease. Conservation programs were also culled and streamlined in the 2014 Farm Bill. Meanwhile, the funding for federal food assistance programs rose from 67% in the 2008 Farm Bill to 80% today.

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program spending as a share of GDP is expected to decline by 9% in 2014. This decrease in spending is largely due to the expiration of temporary benefit increases put in place by the Recovery Act of 2009 during the economic recession. Not only have these temporary benefits expired, but the total number of SNAP recipients has decreased as well. Caseloads skyrocketed during the worst years of the recession, but leveled off in 2011 and began to fall in the first half of 2014. The result will be a reversal of the upward trend SNAP spending has taken in recent years, from $34.6 billion in 2008 to $80 billion in 2012.

While SNAP escaped the $40 billion cut in funding proposed in the version of the bill passed by the House, an estimated $8.5 billion was cut from SNAP benefits over the next decade in the final legislation. By raising the minimum level of heating assistance through LIHEAP (Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program) that qualifies an individual for SNAP, the bill was expected to reduce benefits by about $90 each month for 850,000 households in seventeen states. However, the governors of 12 of the affected states have increased LIHEAP benefits so that their constituents will still be eligible for SNAP. In effect, state governments have reversed the SNAP cuts in the majority of states where they would have occurred.

Sources:

“2014 Farm Bill Drill Down: The Bill by the Numbers.” NSAC’s Blog. National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, 4 Feb. 2014.

“Agricultural Act of 2014: Highlights and Implications.” United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. USDA Economic Research Service, 5 Aug. 2014.

Bolen, Ed, Dorothy Rosenbaum, and Stacy Dean. “Summary of the 2014 Farm Bill Nutrition Title: Includes Bipartisan Improvements to SNAP While Excluding Harsh House Provisions.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. N.p, 3 Feb. 2014.

FitzGerald, Kathleen. “Snapshot of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.” Congressional Budget Office, 16 Apr. 2013.

Johnson, Renee, and Jim Monke. “What is the Farm Bill?” Congressional Research Service, 23 July 2014.

Rosenbaum, Dottie, and Brynne Keith-Jennings. “SNAP Costs Falling, Expected to Fall Further.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 28 May 2014.

http://www.farmland.org/programs/federal/documents/2014_0213_CRS_FarmBillSummary.pdf

http://www.fns.usda.gov/pd/SNAPsummary.htm

http://www.foodsystemsnyc.org/articles/farm-bill-jan-2011

http://nationalaglawcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/assets/crs/RS22131.pdf

http://www.reuters.com/article/2010/04/20/us-usa-farmbill-process-idUSTRE63J5HB20100420